News

The latest insights, sector developments and case updates from Potter Clarkson. Explore up-to-date content from our experts and stay informed on the issues shaping the IP landscape.

The latest insights, sector developments and case updates from Potter Clarkson. Explore up-to-date content from our experts and stay informed on the issues shaping the IP landscape.

A decision of the EPO Opposition Division (OD) can be appealed, but only by a party who took part in the opposition proceedings and is adversely affected by the decision.

An EPO opposition and an EPO appeal are distinct procedures, each with its own character, timetable, evidential rules, and decision-making body.

The reason you started your business was to bring your garments, materials and manufacturing innovations to market so the largest possible number of people can enjoy them.

The Ideas Powered for Business SME Fund is a grant scheme designed to assist EU and Ukraine-based small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in protecting their intellectual property (IP) rights.

.jpg)

The latest edition of the Nice Classification, the international system used to classify goods and services for trade mark registration, entered into force on 1 January 2026.

In December 2025, EU lawmakers reached a provisional agreement on the long-anticipated regulation of plants developed using so-called new genomic techniques (NGTs) such as targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis that enable plant breeders to make precise changes to a plant’s genome without introducing foreign genetic material.

.jpg)

In 2025, the global sports industry stands at a pivotal crossroads.

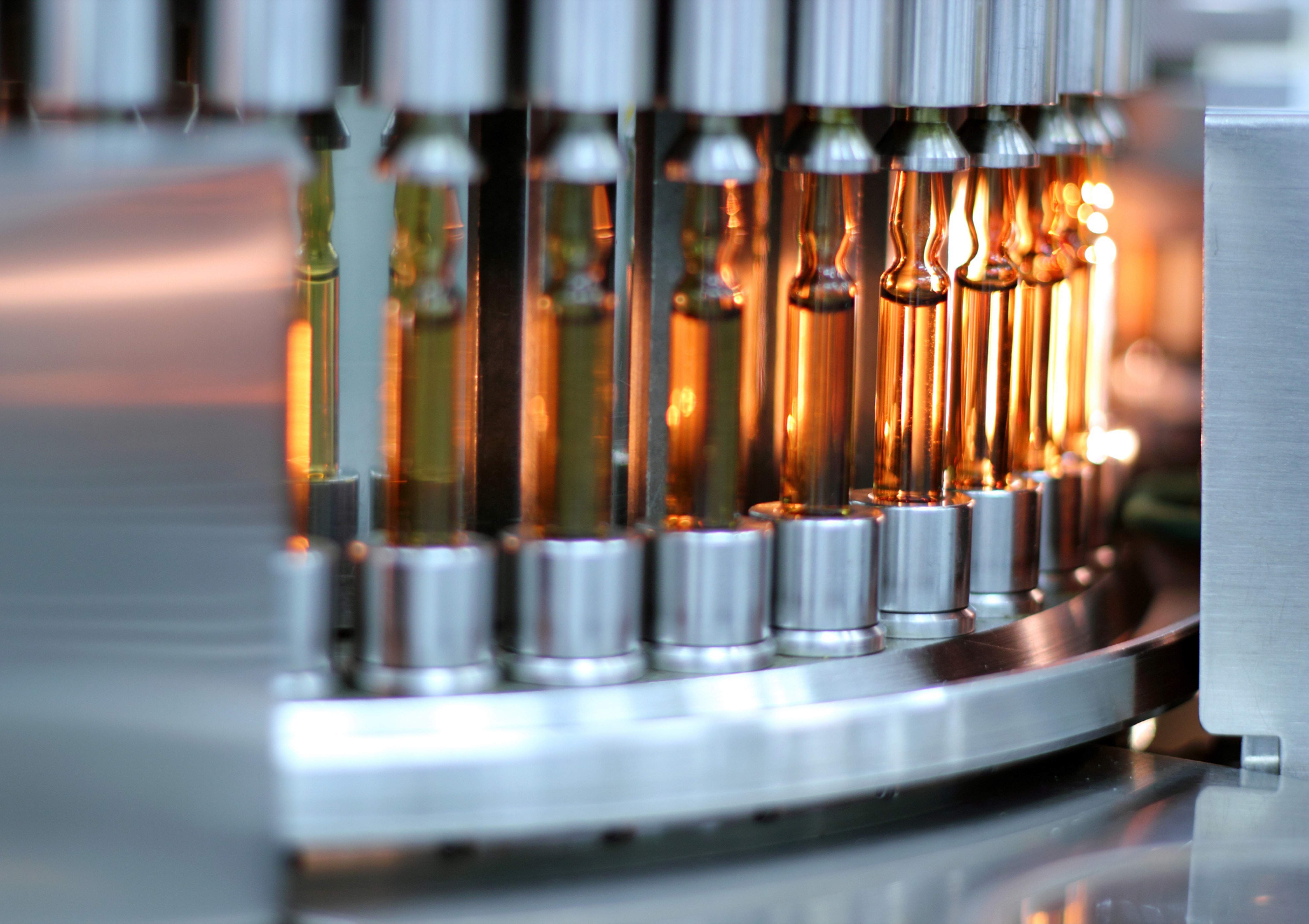

In a significant milestone, the European Parliament and Council reached a provisional agreement on the EU “pharma package” on 11th December 2025.

%203.jpg)

The new .MOBILE domain has launched opening up a major opportunity for brands operating in mobile-focused sectors. As digital experiences continue shifting toward mobile-first engagement, this new domain extension represents more than just another naming option. It represents a strategic investment in the future of your online identity.

.jpg)

Counterfeits have always come with their own vocabulary. Over the last few years words like “knockoffs,” “reps” or “replicas” and even - somewhat cheekily - “inspired” have been eclipsed by “dupes”. It’s a well-chosen term.

%20(1).jpg)

First UK ruling on SPC manufacturing waivers aligns with EU case law trends and rejects restrictive German approach.

Strong branding is what makes your products or services stand out: distinctive names, logos, and designs are key to building recognition and trust. Protecting that identity through trade marks is essential. But big changes are coming at the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) that every business should know about.

Most of us start in research with big dreams—curing cancer, tackling climate change, creating something that matters. In engineering biology, those dreams feel closer than ever. But publishing your work doesn’t guarantee impact.

The UPC Court of Appeal has overturned a decision of the Lisbon Local Division and granted Boehringer Ingelheim (“Boehringer”) a provisional injunction for imminent patent infringement. In doing so, it has confirmed that completion of national pricing and reimbursement procedures for generic drugs may be sufficient to trigger injunctive relief.

We’re proud to announce that Potter Clarkson has once again been recognised in the Chambers UK Guide 2026.