In a recent judgment surrounding ophthalmic pharmaceutical product manufacturer Santen, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has further limited opportunities for pharmaceutical companies to obtain Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) for new applications of old products.

The prohibitive nature of the decision effectively overturns the 2012 Neurim judgment in this area and calls into question the validity of SPCs granted for new indications of products which had previously received a marketing authorisation (MA) in the EU.

Background

A fundamental requirement for obtaining an SPC is that the MA relied upon is the first authorisation to place the product on the market as a medicinal product (Article 3(d) of Regulation (EC) No 469/2009). Article 1(b) further defines the term “product” as only “the active ingredient or combination of active ingredients of a medicinal product” and not any non-active ingredients such as excipients or adjuvants.

In its landmark July 2012 judgment in the case of Neurim (C-130/11), the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) effectively ‘relaxed’ European SPC law in favour of innovators by ruling that:

“the mere existence of an earlier marketing authorisation obtained for a veterinary medicinal product does not preclude the grant of [an SPC] for a different application of the same product for which [an MA] has been granted, provided that the application is within the limits of the protection conferred by the basic patent relied upon for the purposes of the application for the [SPC]”.

Neurim’s SPC for melatonin for use in treating insomnia in humans was accordingly deemed allowable despite there being a previous MA covering melatonin for use in regulating fertility in sheep.

This decision had been interpreted by many to mean that a MA for a new “application” of a previously authorised product could support the grant of an SPC despite the tough literal wording of Article 3(d) of the SPC Regulation. Nevertheless, the applicability of the rationale of Neurim was subsequently curtailed in the CJEU’s March 2019 judgment in Abraxis (C-443/13), and has now been effectively eliminated with the CJEU’s present decision on this issue.

The facts and arguments

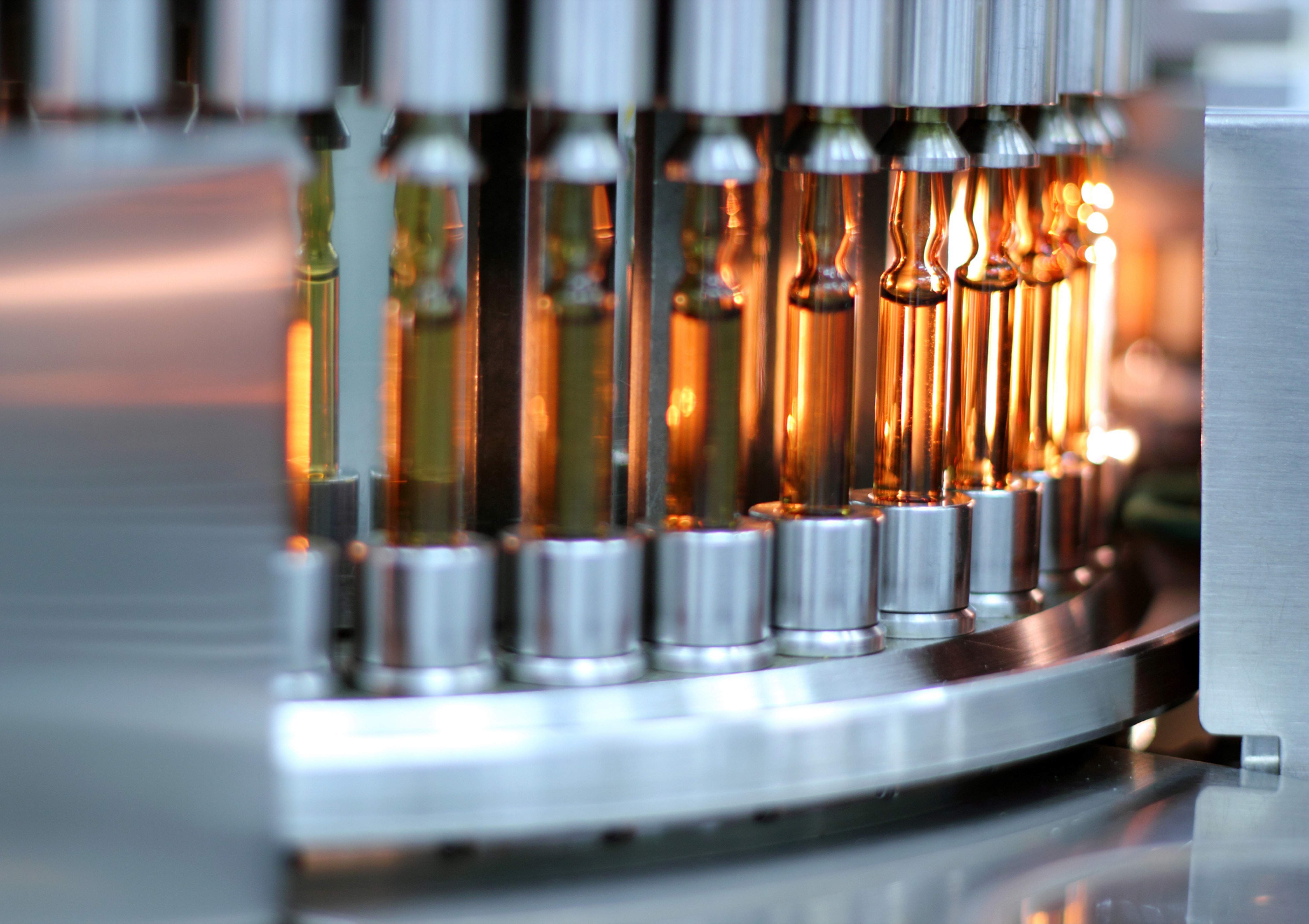

The Santen case (C-673/18) relates to the company’s application for an SPC covering its Ikervis® product – an emulsion containing ciclosporin, authorised for the treatment of severe keratitis in adults with dry eye disease. The claims of Santen’s patent (EP 1 809 237) cover ophthalmic oil-in-water emulsions (including those with immunosuppressive agents such as ciclosporin) and their use to treat ocular conditions.

The French National Institute of Intellectual Property (INPI) refused Santen’s SPC application because the active ingredient ciclosporin had previously been authorised in the form of capsules or an oral solution as the product Sandimmun® for the treatment of endogenous uveitis (an inflammatory disorder of the middle layer of the eye).

In the subsequent appeal proceedings, the Court of Appeal of Paris referred questions to the CJEU about the definition of “different application” in the context of Neurim. The first question included a reiteration of the question answered in Abraxis, namely whether a new formulation can be considered a “different application” under Neurim. Santen argued that its Ikervis® product was not only a new formulation but also one that was authorised for a new therapeutic use as the product is used to treat a different disease and is administered by a different route (eye drops rather than oral administration).

Judgment

In its latest ruling, the CJEU decided that:

“Article 3(d) of [the SPC Regulation] for medicinal products must be interpreted as meaning that a marketing authorisation cannot be considered to be the first marketing authorisation, for the purpose of that provision, where it covers a new therapeutic application of an active ingredient, or of a combination of active ingredients, and that active ingredient or combination has already been the subject of a marketing authorisation for a different therapeutic application.”

This conservative decision follows in the footsteps of the Abraxis case but goes further still. While the Abraxis decision specifically precludes SPCs for “a new formulation of an old active ingredient”, the present judgment now precludes SPCs covering “a new therapeutic application of an active ingredient” where an MA has previously been granted. In doing so, the Court specifically rejects the basic rationale of Neurim that involved determining whether the MA relied upon is the first to fall within the scope of the basic patent (see paragraphs 53 and 60), returning us to a literal reading of Article 3(d).

In support of its decision, the Court relied again on the Explanatory Memorandum behind the SPC Regulation, arguing that the SPC system was devised to reward the bringing of new active ingredients (or new combinations thereof) to the market, including repurposing old active ingredients that had not previously been authorised for any medicinal use. The Court also sought to avoid compromising the “simplicity and predictability” of the SPC system, suggesting that the introduction of a distinction between different therapeutic applications could lead national offices to adopt complex and divergent positions.

Implications

While the Abraxis ruling seemed to at least partially frustrate the opportunities opened up by Neurim, the judgment in Santen arguably closes the door completely. Neurim first provided that grant of an MA for a “different application” may allow grant of an SPC, and the CJEU’s use of similar language in the Santen judgment leaves little room for manoeuvre.

The Santen decision makes several references to Neurim, but ultimately dismisses the premise that it may be possible to obtain an SPC for a new therapeutic application of an active ingredient that has already been the subject of an earlier MA. It appears that the present judgment simply cannot be squared with Neurim, which calls into question the validity of a number of SPCs that had been granted on that basis.

In comparison to Sandimmun®, Santen’s Ikervis® product involved a different formulation, administered via a different route to a different site of treatment and for a different indication. There now appears to be no circumstance in which a new MA for a previously authorised medicinal product may confer eligibility for an SPC.

Accordingly, SPCs will now need to be based on the first MA for an active ingredient, regardless of its therapeutic application. Of course, to the extent that a subsequent MA falls within the scope of the basic patent upon which an SPC is based (referring to the first MA), the scope of that SPC would extend to cover the subsequent MA. However, this would require the subsequent MA to be authorised before expiry of the SPC which may not always be the case.

The Court acknowledges that a first MA for a product that was already known but that had not previously been authorised as a medicinal product can nevertheless give rise to an SPC, but this may offer little real comfort for innovators.

Manufacturers of generic products will most likely welcome this decision and may seek to utilise it to challenge the validity of SPCs directed to previously authorised active ingredients.

Further reading

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02009R0469-20190701

- http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=125216&pageIndex=0&doclang=en&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=8812993

- http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=212011&pageIndex=0&doclang=en&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=8812643

- https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=EP&NR=1809237B1&KC=B1&FT=D&ND=4&date=20081231&DB=&locale=en_EP

- http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=228371&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=8685104

%20(1).jpg)