News

The latest insights, sector developments and case updates from Potter Clarkson. Explore up-to-date content from our experts and stay informed on the issues shaping the IP landscape.

The latest insights, sector developments and case updates from Potter Clarkson. Explore up-to-date content from our experts and stay informed on the issues shaping the IP landscape.

.jpg)

In today’s increasingly knowledge-driven economy, intangible assets often matter more than the more traditional physical ones with companies competing with ideas, innovation and knowhow rather than with factories, machinery or ‘product’ alone.

As Europe accelerates toward a net zero future, few climate solutions have seen momentum quite like biochar.

Innovation in sportstech is accelerating at an extraordinary pace.

On 11 February, the UK Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling in Emotional Perception AI Limited v Comptroller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks¹ that reshapes UK practice on the assessment of computer-implemented inventions, aligning it with the European Patent Office’s long-standing approach.

Fashion is one of the fastest moving industries in the world. Trends shift in days, new brands appear every week and consumers are smarter, more selective and more values driven than ever before.

A decision of the EPO Opposition Division (OD) can be appealed, but only by a party who took part in the opposition proceedings and is adversely affected by the decision.

An EPO opposition and an EPO appeal are distinct procedures, each with its own character, timetable, evidential rules, and decision-making body.

The reason you started your business was to bring your garments, materials and manufacturing innovations to market so the largest possible number of people can enjoy them.

Potter Clarkson is delighted to announce its inclusion in the 2026 edition of the World Trademark Review (WTR) 1000, a leading global guide that highlights the world’s top trade mark professionals and firms.

The Ideas Powered for Business SME Fund is a grant scheme designed to assist EU and Ukraine-based small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in protecting their intellectual property (IP) rights.

.jpg)

The latest edition of the Nice Classification, the international system used to classify goods and services for trade mark registration, entered into force on 1 January 2026.

In December 2025, EU lawmakers reached a provisional agreement on the long-anticipated regulation of plants developed using so-called new genomic techniques (NGTs) such as targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis that enable plant breeders to make precise changes to a plant’s genome without introducing foreign genetic material.

.jpg)

In 2025, the global sports industry stands at a pivotal crossroads.

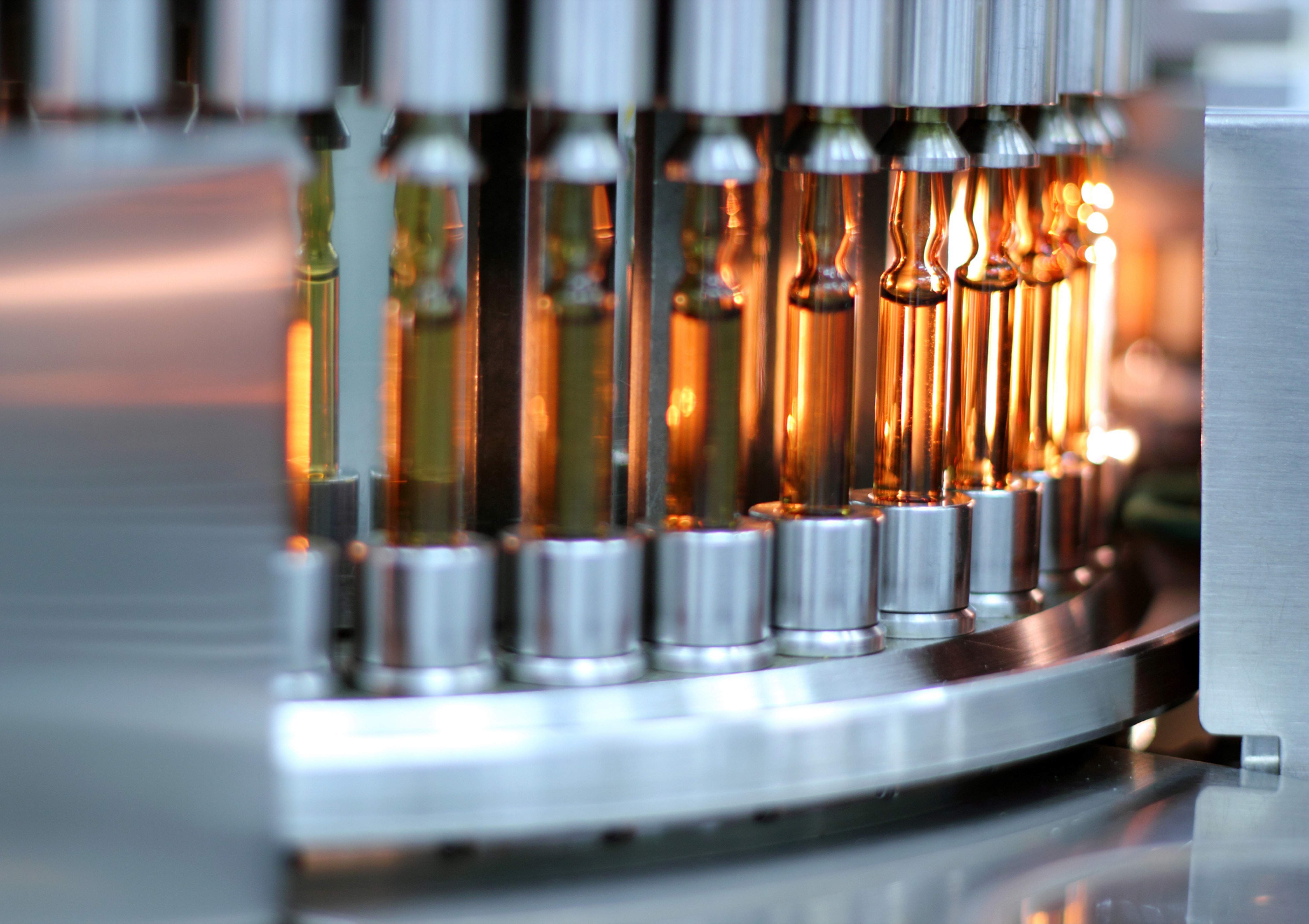

In a significant milestone, the European Parliament and Council reached a provisional agreement on the EU “pharma package” on 11th December 2025.

%203.jpg)

The new .MOBILE domain has launched opening up a major opportunity for brands operating in mobile-focused sectors. As digital experiences continue shifting toward mobile-first engagement, this new domain extension represents more than just another naming option. It represents a strategic investment in the future of your online identity.

.jpg)

Counterfeits have always come with their own vocabulary. Over the last few years words like “knockoffs,” “reps” or “replicas” and even - somewhat cheekily - “inspired” have been eclipsed by “dupes”. It’s a well-chosen term.